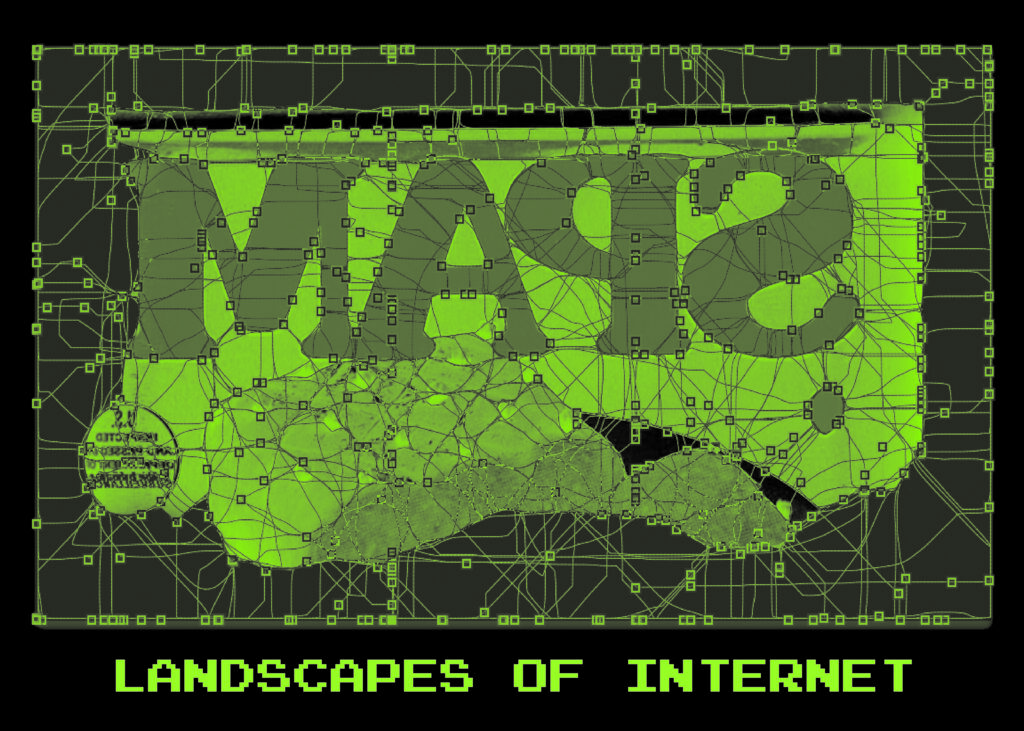

The solo show Landscapes of Internet took place in Kunsthaus L6 Freiburg from June 10 until July 11, 2021 and was curated by Jennifer Krieger.

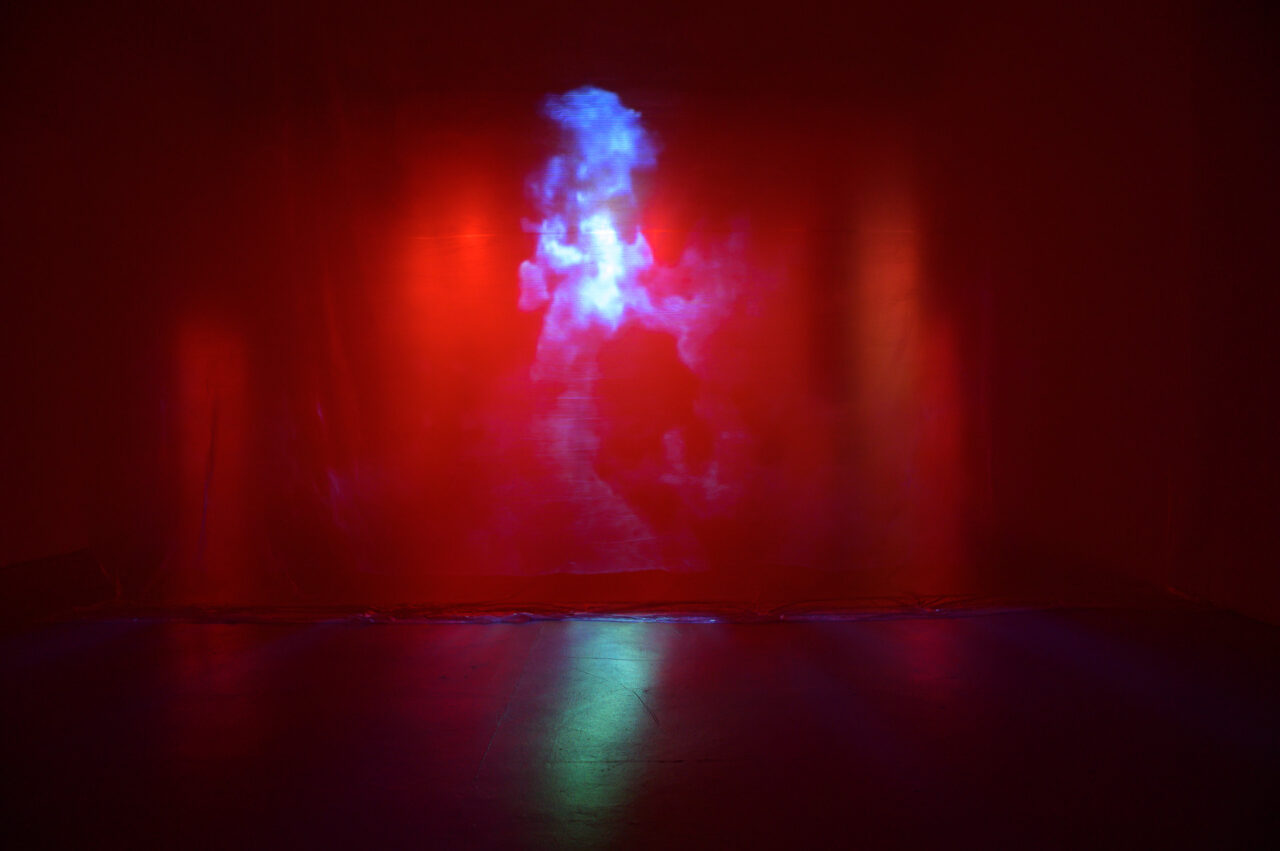

The show took you on a journey to the imaginary of a digital landscape, where you would find yourself confronted with technology and pure natural forces at the same time: the artworks were embedded in an atmosphere of sound, light, wind and smell.

The exhibition followed the ideas of sustainability not only concerning the topic of its content itself, e.g. how to live in times of progressing digitization and consumption of ressources of our planet, but also in the exhibition making: all material was borrowed, recycled or re-used.

About the theoretical reflections Jennifer and me published a text in frame-less magazine, which you can read here.

The following video takes you on a short trip through the exhibition. For the best audio experience I recommend wearing headphones.

The video recording was done with help of Michaela Klähn, the sound-of-Internet editing by Vincent Wikström.

The question of possibilities, potentials and limits of space are at the center of the exhibition LANDSCAPES OF INTERNET. Starting from observations on current hypertopization effects of digitality, Sophie Innmann explores virtual as well as analog spaces in terms of their commonalities, differences and compatibility from the specific perspective of human perception. The possibilities, but also the limits of a real space are critically questioned by the artist. The reflections on this are influenced by the experiences of the social pandemic turn, but reach back even further: already in pre-Covid times, Innmann reflected on the existing paradigm of real (museum) space in her artistic production by questioning the specific characteristics of the institutional exhibition space: Where does this system reach its limits? What is special about the digital space? The exhibition in L6 aims to provide access to this intangible world of the Internet. Haptic, audio-visual experiences are combined with technological loopholes that allow a temporary opening of virtual space in real space. A walk through the landscape designed by Innmann thus re-creates a reference to a tangible reality by making the digital visible in accessible objects.

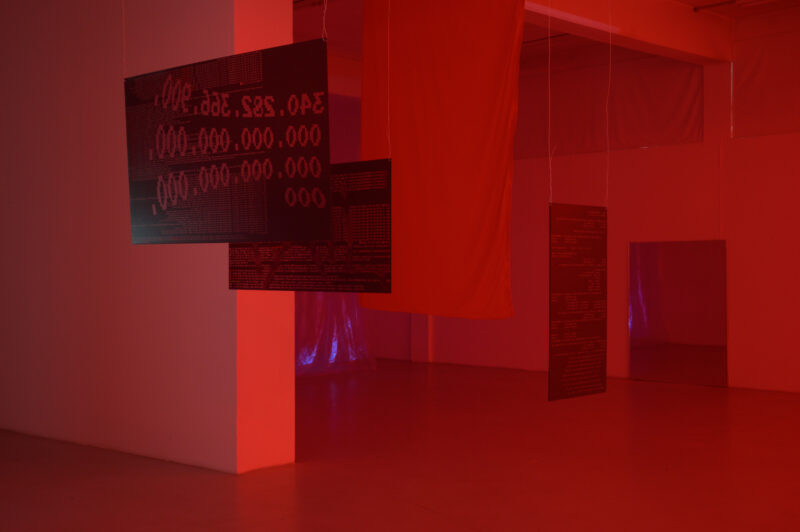

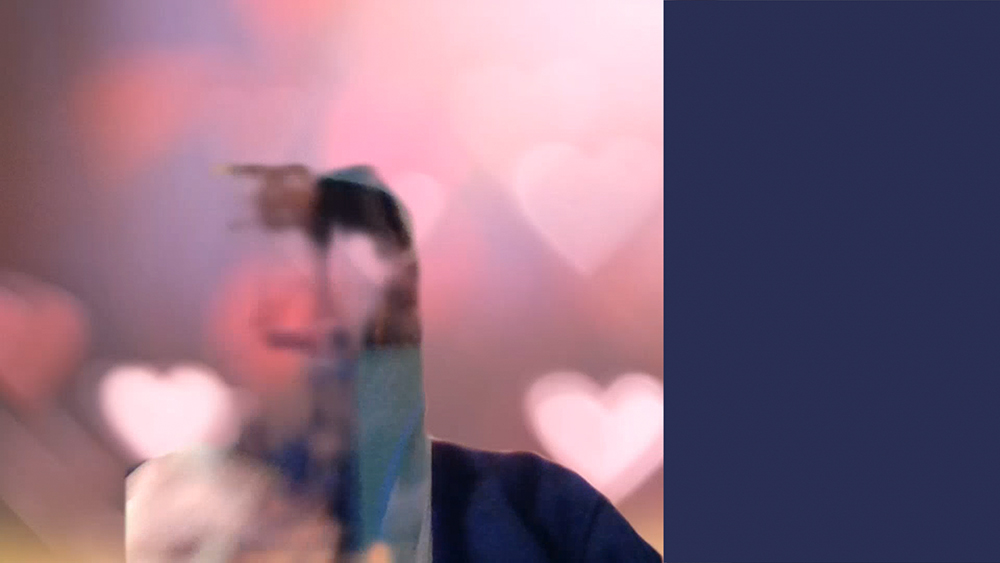

Visitors gain access only by crossing the firewall in the entrance area; the exhibition space itself is visually bathed in a subdued, atmospheric light. The other world, that of digital space, is made clear by a pervasive soundscape (The Sound of Internet, sound-engineering: Vincent Wikström). The omnipresence of the digital becomes palpable and a holistic, sensory experience. Innmann leaves the verification of whether one is granted or denied access to this world not to the system, but to the visitors themselves. The red flag (verification – red flag by default) is both a warning and an indicator of a potential threat. The view into the mirror runs into the void, respectively into the infinite space, which, however, obviously only represents an optical illusion. The series camouflage shows stills taken from a cloud-based video conferencing service in which virtual meetings are made possible. The true, direct encounter, however, remains absent in this format – through rapid movements, the artist manages to elude the camera and to conceal her identity, at least temporarily. Blurred, graphic images of her person emerge – pixelated fragments that remind us how much or how little each person is transmitting as data at this moment.

The critical questioning of the transparent user, who often carelessly feeds information into the digital system and feeds the virtual cloud with considerable amounts of data, is taken up in several of Innmann’s works. A laser beam hits surfboards and explicitly points to the process of scanning data and personal information (A user’s life), an unstoppable process in which users further chain themselves with every click and seemingly merge with the digital world (Fusion).

But is it possible to counteract this appropriation, to escape the algorithm and find anonymity behind IP addresses (no such user found)? Or does one remain trapped and henceforth move in an in-between space that is able to cleverly evade any approach and in this sense only represents a projection of an apparent reality (hypertopia)?

The walk through the exhibition ends with a return to existential elements of nature and thus inevitably refers to the overcoming of the wall of fire at the beginning of the exhibition. Tree trunks lie charred and burned out on the floor, a backhoe shovel placed next to them (Netflix and Chill). Not only is the exploitation of natural resources through the daily use of the Internet and the energy consumption of data storage devices brought to mind here, but also one’s own personal burnout, which has led to a routinized automatism. Innmann does not present an obvious strategy for overcoming this state; rather, she captures this feeling as a lasting disturbance: an incisive noise that forces a pause, a moment of pause (cloud calling).

Text: Jennifer Krieger, 2021